Today is a historic day. The Confederate monument that has stood in Arlington National Cemetery for nearly 110 years is being removed. While observers waited on the injunction against removal to be lifted, I wrote this piece (below) about its history, the narrative that swirls around this particular removal, and the real meaning of reconciliation.

No sooner had workers begun the work of dismantling the Confederate monument at Arlington on Monday, than a federal judge issued a temporary restraining order halting the removal of one of the nation’s most prominent memorials to the Confederacy located on federal property.

Defend Arlington, the organization that brought the lawsuit against the Defense Department, claims that the removal had been “rushed,” even though the recommendation for removal came in August 2022 in the report filed by the Department’s Naming Commission. Still, it is the claim the Confederate memorial stands as a tribute to reconciliation where the historical narrative gets messy.

In his interview with the Washington Post, Scott Powell, a spokesman for Defend Arlington argued that the Confederate memorial simply represents “peace and reconciliation,” part of a narrative that’s been made in conservative circles as the time of removal has inched closer. On X, Matt Walsh repeated the message that the Arlington monument is a “Reconciliation Monument.” Both are a reference to sectional reconciliation between North and South fifty years after the Civil War.

What these defenders of removal do not have on their side are the facts of history.

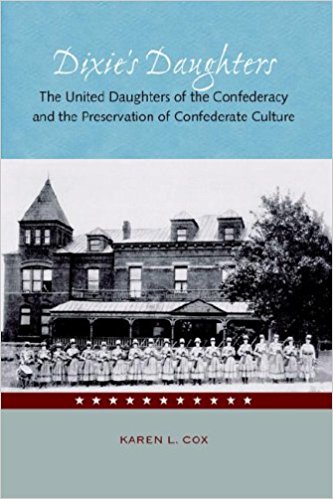

Many of them point to President William McKinley’s 1898 speech in Atlanta that the federal government “should share . . . in the care of graves of Confederate soldiers.” This was not an invitation to build a Confederate memorial in Arlington National Cemetery but the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) ran with it. In the fall of 1906, only a few months after Congress passed a law allowing the bodies of 267 Confederate soldiers buried on northern battlefields to be reinterred in a newly-designated section of the cemetery, local members of the UDC formed the Arlington Confederate Monument Association and engaged in a years-long fundraising campaign for the monument that is currently in litigation.

The Daughters were the first to suggest that the monument was a memorial of “peace and reconciliation,” which held a very different meaning in the early years of the twentieth century. The organization’s underlying goal since its formation in 1894 was not simply to honor their Confederate ancestors but to seek vindication for them and their cause. For white southerners vindication of the Confederacy became the clearest path to sectional reconciliation and a truly reunited country.

It meant that white northerners had to come around to white southerners’ way of thinking. Former Confederates weren’t “rebels” but “patriots.” And what did vindication look like? The Confederate monument in Arlington National Cemetery is a clear illustration.

Moses Ezekiel, the monument’s sculptor, called his design “New South.” Yet it is clearly a Lost Cause interpretation of the Old South and the Civil War and acts as a pro-Confederate textbook cast in bronze. Hilary Herbert, a former secretary of the U.S. Navy and an advisor to the Arlington Confederate Monument Association, made that clear when he referred to the statue as “history in bronze.”

Many Daughters were loath to speak of reconciliation even at the time of the monument’s unveiling. They resented that their ancestors had ever been referred to as “traitors.” Had not the South, they asked, fought in defense of the Constitution? Of course, they meant the Tenth Amendment protecting states’ rights—the same amendment they believed gave them the right to enslave human beings.

The Arlington monument helped assuage those feelings of resentment, because it represented Confederate heroism and not its disloyalty. There was also its placement on a landscape of national significance, which suggested to them that the North recognized the “truth” about the South. Marion Butler, the U.S. senator from North Carolina, explained it this way: “The whole spirit of the thing [referring to the monument] has been fostered by northerners, and they have helped the monument association in every way to bring its purpose to a grand success.”

What current politicians and conservatives are calling a “monument of reconciliation” or a “reconciliation monument” tells only part of the story. The terms of reconciliation were decided by former Confederates and the women who raised the money to build the Confederate monument in Arlington National Cemetery, which they presented as a “gift to the nation” in 1914.

And the terms were met. The nation’s cemetery became home to a memorial that vindicated the Confederate cause where it has remained for more than a century.

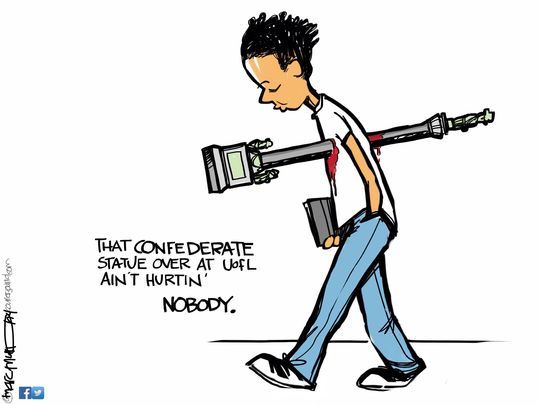

Its removal, however, will be the true reconciliation, because the Confederacy will no longer be venerated nor maintained by our federal government.

When the monument to Robert E. Lee was unveiled in Richmond in 1890, African Americans in that city recognized it as a symbol of their own oppression and its links to suppressing their right to vote. Barely a week after unveiling of the Lee Monument, John Mitchell, Jr. the editor of the black newspaper the Richmond Planet, penned an editorial in which he warned readers that the rights blacks had won during Reconstruction were being rolled back, especially the right to vote. “No species of political crimes has been worse than that which wiped the names of thousands of bona-fide Colored Republican voters from the Registration books of this state,” Mitchell wrote. He claimed, rightly, that refusing to allow black men to vote was a “direct violation of the law,” and blamed state officials sworn to uphold the U.S. Constitution for illegally scrubbing the names of men from voter rolls, marking them “dead” or having moved to another state, when neither was true.

When the monument to Robert E. Lee was unveiled in Richmond in 1890, African Americans in that city recognized it as a symbol of their own oppression and its links to suppressing their right to vote. Barely a week after unveiling of the Lee Monument, John Mitchell, Jr. the editor of the black newspaper the Richmond Planet, penned an editorial in which he warned readers that the rights blacks had won during Reconstruction were being rolled back, especially the right to vote. “No species of political crimes has been worse than that which wiped the names of thousands of bona-fide Colored Republican voters from the Registration books of this state,” Mitchell wrote. He claimed, rightly, that refusing to allow black men to vote was a “direct violation of the law,” and blamed state officials sworn to uphold the U.S. Constitution for illegally scrubbing the names of men from voter rolls, marking them “dead” or having moved to another state, when neither was true.

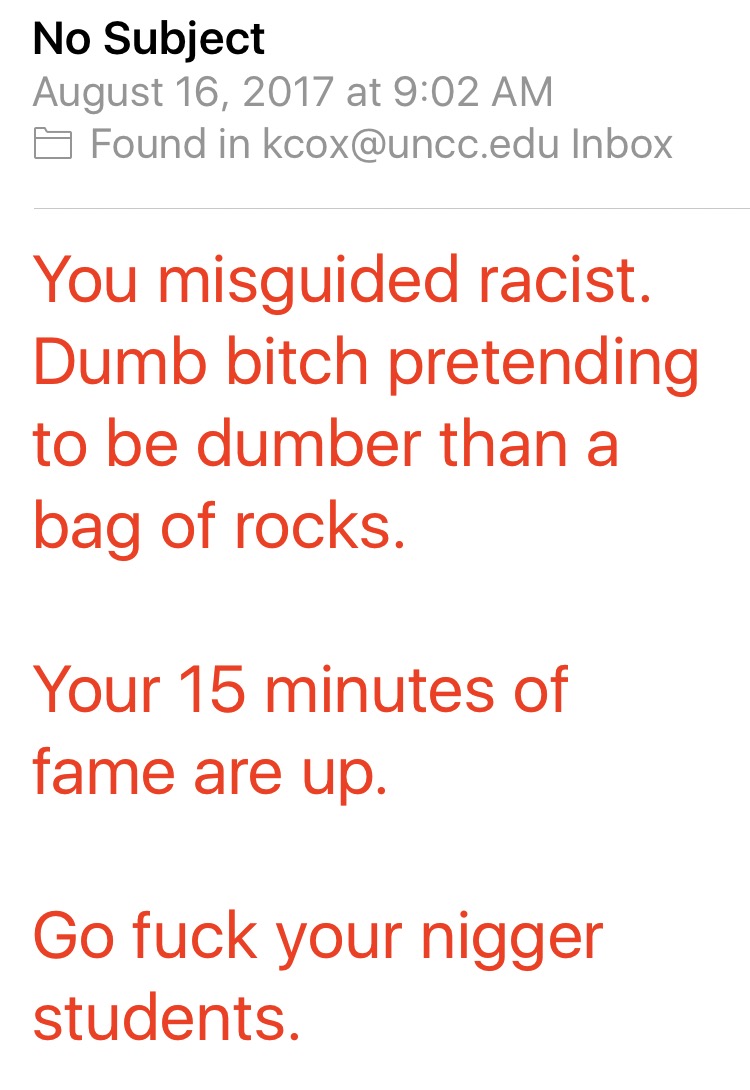

I say that knowing that whatever courage I showed pales by the courage it takes to simply be black in today’s America. I benefit from and am protected by white privilege. What I wrote about Confederate monuments cannot be equated with how black southerners must feel in seeing these tangible reminders of their treatment at the hands of people who did not, and still do not, care about their humanity.

I say that knowing that whatever courage I showed pales by the courage it takes to simply be black in today’s America. I benefit from and am protected by white privilege. What I wrote about Confederate monuments cannot be equated with how black southerners must feel in seeing these tangible reminders of their treatment at the hands of people who did not, and still do not, care about their humanity.