Over the past few weeks, Americans have watched as Black Lives Matter protests have turned on Confederate monuments, vandalizing them, tearing them down, spraying them with graffiti with messages to end police brutality or to call out the racism that is tearing our country apart.

As a result, several municipalities across the South have begun to take local action to remove their monuments, often located on courthouse lawns or along public thoroughfares. Doing so means to defy state laws, some of which were passed in the aftermath of the Charleston Massacre of nine parishioners inside Emmanuel AME Church five years ago.

Today voter suppression in several states, made worse by gerrymandered districts like in my home state of North Carolina, makes it difficult to near impossible to elect officials who will change laws, including those intended to preserve Confederate monuments. In fact, the history of Confederate monuments is tied directly to the disenfranchisement of black voters and has been since the 1890s.

When the monument to Robert E. Lee was unveiled in Richmond in 1890, African Americans in that city recognized it as a symbol of their own oppression and its links to suppressing their right to vote. Barely a week after unveiling of the Lee Monument, John Mitchell, Jr. the editor of the black newspaper the Richmond Planet, penned an editorial in which he warned readers that the rights blacks had won during Reconstruction were being rolled back, especially the right to vote. “No species of political crimes has been worse than that which wiped the names of thousands of bona-fide Colored Republican voters from the Registration books of this state,” Mitchell wrote. He claimed, rightly, that refusing to allow black men to vote was a “direct violation of the law,” and blamed state officials sworn to uphold the U.S. Constitution for illegally scrubbing the names of men from voter rolls, marking them “dead” or having moved to another state, when neither was true.

When the monument to Robert E. Lee was unveiled in Richmond in 1890, African Americans in that city recognized it as a symbol of their own oppression and its links to suppressing their right to vote. Barely a week after unveiling of the Lee Monument, John Mitchell, Jr. the editor of the black newspaper the Richmond Planet, penned an editorial in which he warned readers that the rights blacks had won during Reconstruction were being rolled back, especially the right to vote. “No species of political crimes has been worse than that which wiped the names of thousands of bona-fide Colored Republican voters from the Registration books of this state,” Mitchell wrote. He claimed, rightly, that refusing to allow black men to vote was a “direct violation of the law,” and blamed state officials sworn to uphold the U.S. Constitution for illegally scrubbing the names of men from voter rolls, marking them “dead” or having moved to another state, when neither was true.

Mitchell’s words were prophetic as he identified what was essentially a backlash against black progress.

In the decade following the Lee Monument’s unveiling, one southern state after another passed laws disenfranchising black men, a right that was guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment. The elimination of black voters, not only by law but through violent white supremacy, and the creation of Jim Crow legislation that limited black freedom, all occurred during the very same years that the hundreds of Confederate monuments now at issue were built across the South. And black southerners did not have a say in the matter, because their rights as citizens had been obliterated. Even in towns where they represented the majority of the population, they could not vote to prevent them from being built in the center of towns where they lived, they could not petition to have them removed, and they could not protest them publicly out of fear of reprisal, although they found ways of doing so out of the view of southern whites.

Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and especially the Voting Rights Act of 1965, black southerners not only voted, but elected people to office who looked like them. Local city councils increasingly had black representation and over the course of the next few decades African Americans throughout the region challenged the existence of Confederate symbols on the grounds of local and state government, which were supposed to be democratic public spaces that represented all citizens.

But in the 1990s, as in the 1890s, Republicans found another way to constrict black political power via majority/minority districts. This form of gerrymandering, sometimes called affirmative gerrymandering, did not violate Voting Rights Act regulations. Rather, it consolidated the minority vote, limiting a black majority to one district. As political scientist Angie Maxwell explains, while these new lines ensured minority representation, “it bleached the other districts white, allowing the GOP to pick up seats fast in the South.” The result in 1994 was the Republican takeover of the House.

This model of Republican-favored gerrymandering grew worse in the South in the early twentieth-first century, and its implementation not only guaranteed more GOP seats in Congress, it led to a similar plan that ensured GOP majorities at the state level. And these are the very state legislatures that passed monument laws designed to preserve Confederate monuments in publicly owned spaces.

The gutting of the Voting Rights Act in 2013 in the context of Confederate monument removal is critical to our understanding of this moment of protests. By suppressing the rights of black voters, as well as white voters who support this movement, GOP-led state legislatures have not only prevented these voters from exercising their rights as citizens, they have usurped local control to remove monuments legally. In essence, they have left no other options for redressing this issue than to take to the streets to demonstrate their frustration.

Still, there have been signs in the last few weeks that there are cracks in the system, as local communities across the South have begun the process of removing their monuments, even in defiance of state laws. In Alabama, the cities of Birmingham, Huntsville, and Mobile have taken action to remove their monuments and accept the $25,000 fine the state imposes for such action. In North Carolina, the law preventing removal of “objects of remembrance” is so imprecise that the towns of Asheville, Rocky Mount, and Salisbury are testing its limits by voting to remove their monuments.

Monuments are ultimately local objects and what becomes of them will be determined by the local communities in which they reside. And while it appears that the tide has turned, as several southern cities and towns have voted or are voting to remove monuments, the state laws remain a barrier to removal.

There also exists a very real concern that once GOP-led southern legislatures return to session, Republicans will close any existing loopholes in monument legislation, which will represent yet another backlash to progress. And once again, there will be no legal redress. And given voter suppression, it removes the possibility of electing officials to amend laws that allow local communities to decide the fate of Confederate monuments.

Under those circumstances, the cycle of protest will likely begin again.

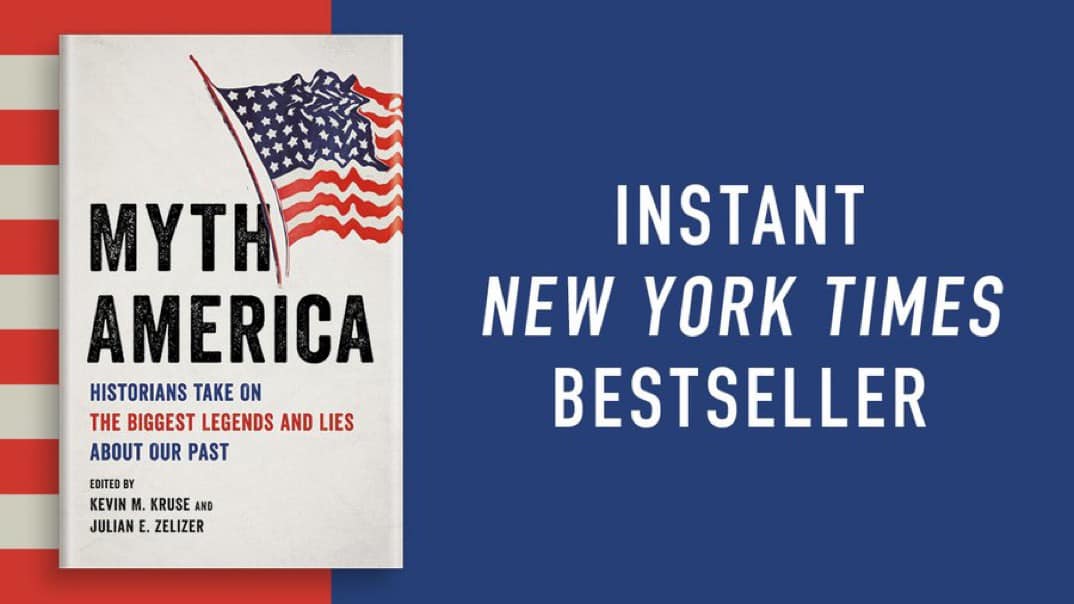

The first was to contribute an essay to a book about myths in American history, edited by Princeton historians Kevin Kruse and Julian Zelizer. I wrote about Confederate monuments as an expression of the Lost Cause myth. This past week that book, Myth America: Historians Take on the Biggest Legends and Lies About Our Past, became an instant best seller on the New York Times bestseller list for nonfiction books, coming in at #8.

The first was to contribute an essay to a book about myths in American history, edited by Princeton historians Kevin Kruse and Julian Zelizer. I wrote about Confederate monuments as an expression of the Lost Cause myth. This past week that book, Myth America: Historians Take on the Biggest Legends and Lies About Our Past, became an instant best seller on the New York Times bestseller list for nonfiction books, coming in at #8. produced by the Atlanta History Center (AHC) and its VP of Digital Storytelling, Kristian Weatherspoon. This past week I got to attend the film’s premiere at the AHC. It was such a wonderful event and a real celebration of the work that public history institutions can do, plus I got to meet a personal heroine of mine, Sally Yates, the former United States Deputy Attorney General and Acting Attorney General who stood up to former President Trump’s so-called “Muslim ban.” She was dismissed for doing so, but I regarded it as an act of moral courage. We need more of that in today’s world.

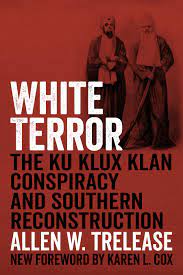

produced by the Atlanta History Center (AHC) and its VP of Digital Storytelling, Kristian Weatherspoon. This past week I got to attend the film’s premiere at the AHC. It was such a wonderful event and a real celebration of the work that public history institutions can do, plus I got to meet a personal heroine of mine, Sally Yates, the former United States Deputy Attorney General and Acting Attorney General who stood up to former President Trump’s so-called “Muslim ban.” She was dismissed for doing so, but I regarded it as an act of moral courage. We need more of that in today’s world. Then last, but not least, I just received my copy of the re-released book White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction by Allen W. Trelease. It was a book I campaigned to have placed back in print, because it remains relative to historical discussions about Reconstruction but also to our contemporary understanding of domestic terrorism. It was an honor for me to write the foreword since Dr. Trelease was a professor and mentor while I was a student in the master’s program in history at UNC Greensboro.

Then last, but not least, I just received my copy of the re-released book White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction by Allen W. Trelease. It was a book I campaigned to have placed back in print, because it remains relative to historical discussions about Reconstruction but also to our contemporary understanding of domestic terrorism. It was an honor for me to write the foreword since Dr. Trelease was a professor and mentor while I was a student in the master’s program in history at UNC Greensboro. When the monument to Robert E. Lee was unveiled in Richmond in 1890, African Americans in that city recognized it as a symbol of their own oppression and its links to suppressing their right to vote. Barely a week after unveiling of the Lee Monument, John Mitchell, Jr. the editor of the black newspaper the Richmond Planet, penned an editorial in which he warned readers that the rights blacks had won during Reconstruction were being rolled back, especially the right to vote. “No species of political crimes has been worse than that which wiped the names of thousands of bona-fide Colored Republican voters from the Registration books of this state,” Mitchell wrote. He claimed, rightly, that refusing to allow black men to vote was a “direct violation of the law,” and blamed state officials sworn to uphold the U.S. Constitution for illegally scrubbing the names of men from voter rolls, marking them “dead” or having moved to another state, when neither was true.

When the monument to Robert E. Lee was unveiled in Richmond in 1890, African Americans in that city recognized it as a symbol of their own oppression and its links to suppressing their right to vote. Barely a week after unveiling of the Lee Monument, John Mitchell, Jr. the editor of the black newspaper the Richmond Planet, penned an editorial in which he warned readers that the rights blacks had won during Reconstruction were being rolled back, especially the right to vote. “No species of political crimes has been worse than that which wiped the names of thousands of bona-fide Colored Republican voters from the Registration books of this state,” Mitchell wrote. He claimed, rightly, that refusing to allow black men to vote was a “direct violation of the law,” and blamed state officials sworn to uphold the U.S. Constitution for illegally scrubbing the names of men from voter rolls, marking them “dead” or having moved to another state, when neither was true.

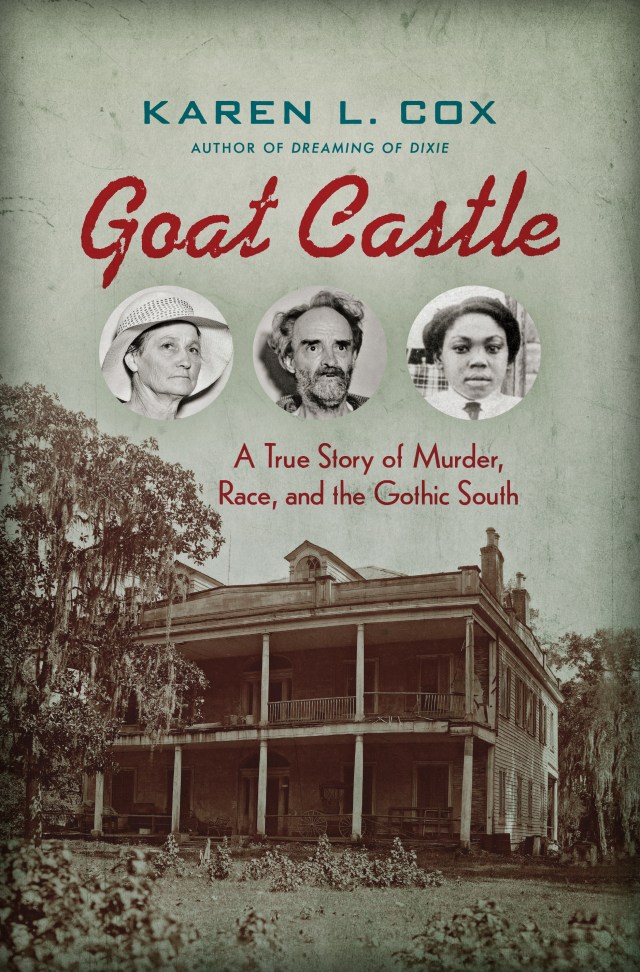

Writing Goat Castle was the most rewarding endeavor of my career. I met wonderful people in Natchez, got to know descendants of one of the principals in the book, and was able to write a book that most people have found accessible. Everyone from my Aunt Wilma to my hairdresser seems to like it, and not just because they know me.

Writing Goat Castle was the most rewarding endeavor of my career. I met wonderful people in Natchez, got to know descendants of one of the principals in the book, and was able to write a book that most people have found accessible. Everyone from my Aunt Wilma to my hairdresser seems to like it, and not just because they know me. Consider the design of

Consider the design of  The revised design got it right, because this was a book about how the South had been romanticized in American popular culture prior to the advent of television. Here’s Miss Southern Belle strumming her banjo, sitting on some oversized cotton bolls and gazing out on a bucolic southern landscape. Even the clouds look like cotton. The art work is adapted from the sheet music for the song “

The revised design got it right, because this was a book about how the South had been romanticized in American popular culture prior to the advent of television. Here’s Miss Southern Belle strumming her banjo, sitting on some oversized cotton bolls and gazing out on a bucolic southern landscape. Even the clouds look like cotton. The art work is adapted from the sheet music for the song “