Note: This post primarily applies to university presses, since this is where I’ve published.

The design of a book cover should convey the essence of what’s inside and intrigue potential readers (read: buyers). As an author, I’m interested in how a designer visualizes the title and the ideas I’ve expressed in a book I’ve written or edited. This can be both exciting (“The designer got it!”) or worrisome (“Whoa, that’s really off the mark!”). It’s a process that I didn’t pay much attention to with my first book, and one I am far more invested in at this point in my career.

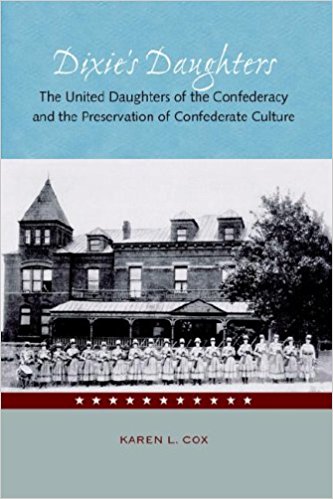

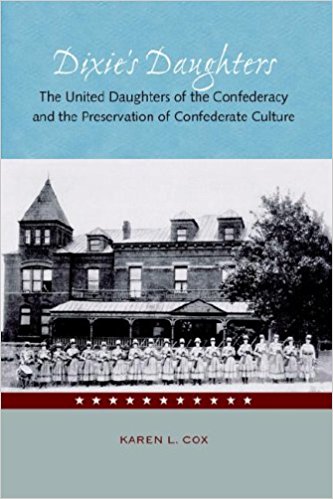

Consider the design of Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture, published in 2003. I didn’t have any quibbles with the font and the designer tried to incorporate some element of Confederate symbolism in the reddish bar below the photograph by adding stars. Stars and bar, anyone? There’s also a Confederate gray, one might say.

Consider the design of Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture, published in 2003. I didn’t have any quibbles with the font and the designer tried to incorporate some element of Confederate symbolism in the reddish bar below the photograph by adding stars. Stars and bar, anyone? There’s also a Confederate gray, one might say.

The photograph, one I found, is from a girls’ school in Texas where the students wore Confederate-inspired uniforms and are all standing at attention with rifles cast over their left shoulders, as though they were members of the CSA. This conveyed a theme in my book, which is that it was women who took on the cause of Confederate memory and, in a sense, they were soldiers in the Lost Cause.

The only issue I had with the cover was that the initial gray color in the title muted my name and it couldn’t be seen. This was upsetting, since it was my first book. It has since been corrected.

My second book Dreaming of Dixie: How the South Was Created in American Popular Culture came out in 2011. A lot had changed since 2003. I was a more mature scholar and while I was open to the designer’s interpretation, it turned out that I needed to weigh in on this decision.

Because there were hundreds of songs written about the South by Tin Pan Alley lyricists, there was an equally large number of sheet music designs from which to draw from. The art of Tin Pan Alley “Dixie songs” were, as you might expect, rich in color and design. Like a book cover, the sheet music art was intended to convey the story told by the song, so the designer had plenty to draw from.

Some of the covers, however, should come with a warning: “Beware of racist caricatures!” It should be implicit, really, but for some reason the initial design for this book actually drew from one of those racist covers. That was when I said “hold up!” The designer clearly misunderstood the implicit message.

The revised design got it right, because this was a book about how the South had been romanticized in American popular culture prior to the advent of television. Here’s Miss Southern Belle strumming her banjo, sitting on some oversized cotton bolls and gazing out on a bucolic southern landscape. Even the clouds look like cotton. The art work is adapted from the sheet music for the song “The Whole World Comes From Dixie (When They Play That Dixie Tune).” No problems with seeing my name here.

The revised design got it right, because this was a book about how the South had been romanticized in American popular culture prior to the advent of television. Here’s Miss Southern Belle strumming her banjo, sitting on some oversized cotton bolls and gazing out on a bucolic southern landscape. Even the clouds look like cotton. The art work is adapted from the sheet music for the song “The Whole World Comes From Dixie (When They Play That Dixie Tune).” No problems with seeing my name here.

My latest book, which presumes there’ll be another out in the ether, is Goat Castle: A True Story of Murder, Race, and the Gothic South. It comes out in October, but I’ve already got a jacket design, because marketing! (Speaking of marketing. . . reviewers, book bloggers, librarians, and other avid readers can now request to see the galleys on NetGalley.)

It’s a true crime story that drew on my skills as a historian, but it is written to be accessible to a broader audience. Set in Depression-era Natchez, Mississippi, it offers insight into the decline of the Old South and southern families, but also about the Jim Crow South and the racial justice that sent an innocent woman named Emily Burns to one of the most notorious prisons in the region at the time, the Mississippi State Penitentiary, better known as Parchman.

This book is very personal to me and so I really wanted the cover to reflect something of the southern gothic drama that unfolded that year, which resulted in national headlines. I also wanted to recognize Emily Burns, who family members called “Sister,” since she was the other victim in this crime. She had to be on the cover. It had taken me five years to find a photograph of her and, more to the point, up until now, community memory had virtually erased her from the story.

First take on the design? No Emily. “It didn’t work. It was confusing. Looks like she was the one murdered,” I was told. “We can put her on the back cover.” No, no, no. This perpetuates her place in the story as being in the background. No. I also worried about the font of the title, so I pushed back. Next take: New font, Emily, and two of the other principals in the case. Much better. Then I gave consideration to the original font design, because I was wrong. It was right on the money, because the font had been adapted from a ticket to Goat Castle (also known as “Glenwood”) in the 1930s. You’ll have to buy the book to learn why there were tickets to Goat Castle.

The final take on the design pushed all of the buttons–southern gothic, image of Goat Castle, the two white principals Dick Dana and Octavia Dockery, but Emily “Sister” Burns was there, too. There was also the font that drew from the ticket. Success!

I’m not suggesting that an author be involved in design. In my case, I’m a historian and so just as I wouldn’t want a designer to correct me about history, it works the same in reverse. At the same time, the book represents you and your work, so when the situation merits your involvement, I believe that you can and should have a honest conversation with your press. Be willing to compromise, however, because your press is responsible for marketing your book.

Feel free to share your own experiences in the comment section below.

Consider, for example, my forthcoming book

Consider, for example, my forthcoming book

As of this writing, the book is three months out. But I can see the light at the end of the tunnel. All of the online retailers (

As of this writing, the book is three months out. But I can see the light at the end of the tunnel. All of the online retailers ( Consider the design of

Consider the design of  The revised design got it right, because this was a book about how the South had been romanticized in American popular culture prior to the advent of television. Here’s Miss Southern Belle strumming her banjo, sitting on some oversized cotton bolls and gazing out on a bucolic southern landscape. Even the clouds look like cotton. The art work is adapted from the sheet music for the song “

The revised design got it right, because this was a book about how the South had been romanticized in American popular culture prior to the advent of television. Here’s Miss Southern Belle strumming her banjo, sitting on some oversized cotton bolls and gazing out on a bucolic southern landscape. Even the clouds look like cotton. The art work is adapted from the sheet music for the song “